Ken Risi

Long-billed Curlew

Long-billed Curlew (Youth) Long-billed Curlew (15 seconds) Long-billed Curlew (30 secondes) Long-billed Curlew

Ken Risi

Long-billed Curlew

Long-billed Curlew (Youth) Long-billed Curlew (15 seconds) Long-billed Curlew (30 secondes) Long-billed Curlew

Amber Fortowsky

Pronghorn

Pronghorn (Youth) Pronghorn (15 seconds) Pronghorn (30 seconds) Pronghorn

Amber Fortowsky

Pronghorn

Pronghorn (Youth) Pronghorn (15 seconds) Pronghorn (30 seconds) Pronghorn

Sugar Maple

Sugar Maple (15 seconds) Sugar Maple (30 seconds) Sugar Maple (long version) Sugar Maple (Youth)

Sugar Maple

Sugar Maple (15 seconds) Sugar Maple (30 seconds) Sugar Maple (long version) Sugar Maple (Youth)

Ryan Hodnett

Northern Leopard Frog

Wetland Wonderland (webisode) Wetlands (30 seconds) Wetlands (60 seconds)

Ryan Hodnett

Northern Leopard Frog

Wetland Wonderland (webisode) Wetlands (30 seconds) Wetlands (60 seconds)

|

| Northern Leopard Frog |

The Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens) is named for its leopard-like spots across its back and sides. Another common name for this frog is the ‘meadow frog’ for its common habitat. Historically, these frogs were harvested for food (frog legs) and are still used today for dissection practice in biology class.

Northern Leopard Frogs are about the size of a plum, ranging from 7 to 12 centimetres. They have a variety of unique colour morphs, or genetic colour variations. They can be different shades of green and brown with rounded black spots across its back and legs and can even appear with no spots at all (known as a burnsi morph). They have white bellies and two light coloured dorsal (back) ridges. Another pale line travels underneath the nostril, eye and tympanum, ending at the shoulder. The tympanum is an external hearing structure just behind and below the eye that looks like a small disk. Black pupils and golden irises make up their eyes. They are often confused with Pickerel Frogs (Lithobates palustris); whose spots are more squared then rounded and have a yellowish underbelly.

|

|

| Colour variations of the Northern Leopard Frog | Pickerel Frog |

Male frogs are typically smaller than the females. Their average life span is two to four years in the wild, but up to nine years in captivity. Tadpoles are dark brown with tan tails.

Cowichan Lake Lamprey

Cowichan Lake Lamprey (Home Grown)

Cowichan Lake Lamprey

Cowichan Lake Lamprey (Home Grown)

|

| Cowichan Lake Lamprey |

Lampreys are an amazing group of ancient fish species which first appeared around 360 million years ago. This means they evolved millions of years before the dinosaurs roamed the earth. There are about 39 species of lamprey currently described plus some additional landlocked populations and varieties.

In general, lamprey are one of three different life history types and are a combination of non-parasitic and parasitic species. Non-parasitic lamprey feed on organic material and detritus in the water column. Parasitic lamprey attach to other fish species to feed on their blood and tissues. This is why lamprey are often unfairly called “aquatic vampires”.

Most, 22 of the 39 species, are non-parasitic and spend their entire lives in freshwater. The remainder are either parasitic spending their whole life in freshwater or, parasitic and anadromous. Anadromous parasitic lampreys grow in freshwater before migrating to the sea where they feed parasitically and then migrate back to freshwater to spawn.

The Cowichan Lake lamprey (Entosphenus macrostomus) is a freshwater parasitic lamprey species. It has a worm or eel-like shape with two distinct dorsal fins and a small tail. It is a slender fish reaching a maximum length of about 273mm. When they are getting ready to spawn they shrink in length and their dorsal fins overlap.

Unlike many other fish species, when lampreys are getting ready to spawn you can tell the difference between males and females. Females develop fleshy folds on either side of their cloaca and an upturned tail. The males have a downturned tail and no fleshy folds. Lamprey don’t have gills like other fish species but have pores for breathing. These seven gill pores are located one after another behind the eye.

There are several characteristics which are normally used to identify lamprey. Many of these are based on morphometrics or measurements, of or between various body parts like width of the eye or, distance between the eye and the snout. Other identifying characteristics include body colour and the number and type of teeth.

Some distinguishing characteristics of this species are the large mouth, called and oral disc and a large eye. This species also has unique dentition. For example, these teeth are called inner laterals. Each lateral tooth has cusps and together they always occur in a 2-3-3-2 cusp pattern.

Annie Langlois

Sea Otter

Sea Otter Sea Otter (Youth) Sea Otter (30 seconds) Sea Otter (15 seconds) Ocean Commotion (webisode)

Annie Langlois

Sea Otter

Sea Otter Sea Otter (Youth) Sea Otter (30 seconds) Sea Otter (15 seconds) Ocean Commotion (webisode)

|

| Sea Otter |

The Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris) is the smallest marine mammal in North America – males measure 1.2 metres in length and weigh an average of 45 kilograms (females are a bit smaller). At the same time, the Sea Otter is the largest member of its family, the mustelids, which includes River Otters, weasels, badgers, wolverines and martens. It’s also the only member of its family that doesn’t need land at all; it’s completely adapted to life in the water. It may come to land to flee from predators if needed, but the rest of its time is spent in the ocean.

The Sea Otter’s fur is one of the thickest in the animal kingdom, with 150,000 or more hairs per square centimetre. It varies in colour from rust to black. Unlike seals and sea lions, the Sea Otter has little body fat to help it survive in the cold ocean water. Instead, it has both guard hairs and a warm undercoat that trap bubbles of air to help insulate it. The otter is often seen at the surface grooming; in fact, it is pushing air to the roots of its fur.

Bill Abbott

Northern Giant Pacific Octopus

Northern Giant Pacific Octopus Northern Giant Pacific Octopus (30 seconds) Northern Giant Pacific Octopus (Youth) Northern Giant Pacific Octopus (15 seconds) Ocean Commotion (webisode)

Bill Abbott

Northern Giant Pacific Octopus

Northern Giant Pacific Octopus Northern Giant Pacific Octopus (30 seconds) Northern Giant Pacific Octopus (Youth) Northern Giant Pacific Octopus (15 seconds) Ocean Commotion (webisode)

|

| Giant Pacific Octopus Underside |

The Northern Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) is a large cephalopod mollusk, which means it’s related to gastropods (snails and slugs) and bivalves (clams and oysters). Mollusks are invertebrates, meaning they have no bones. Insects are also invertebrates, but mollusks differ from insects in that they don’t have an exoskeleton. They are cold-blooded, like all invertebrates, and have blue, copper-based blood. The octopus is soft-bodied, but it has a very small shell made of two plates in its head and a powerful, parrot-like beak.

|

| Anatomy of the Giant Pacific Octopus' head |

The Giant Pacific Octopus is the largest species of octopus in the world. Specimens have weighed as much as 272 kg and measured 9.6 m in radius (although they can stretch quite a bit), but most reach an average weight of only 60 kg. They’re normally reddish-brown in colour.

Susan Enders

Chorus Frogs

Chorus Frogs Chorus Frogs (Youth) Chorus Frogs (15 seconds) Chorus Frogs (30 seconds) Wetland Wonderland (webisode)

Susan Enders

Chorus Frogs

Chorus Frogs Chorus Frogs (Youth) Chorus Frogs (15 seconds) Chorus Frogs (30 seconds) Wetland Wonderland (webisode)

There are two species of chorus frogs here in Canada: the Boreal Chorus Frog (Pseudacris maculata) and the Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris triseriata). Prior to 1989, all Canadian chorus frogs were considered to be one species, as they are very similar – it’s even hard for scientists to differentiate them! Studies determined, though, that they are indeed different. While the Western Chorus Frog might have slightly shorter legs than the Boreal Chorus Frog, and that their respective calls have different structures, genetics have proven this.

| Boreal Chorus Frog (left), Western Chorus Frog (right) |

Chorus Frogs are about the size of large grape, about 2.5cm long on average, with a maximum of 4cm. They are pear-shaped, with a large body compared to their pointed snout. Their smooth (although a bit granular) skin varies in colour from green-grey to brownish. They are two of our smallest frogs, but best ways to tell them apart from other frogs is by the three dark stripes down their backs, which can be broken into blotches, by their white upper lip, and by the dark line that runs through each eye. Their belly is generally yellow-white to light green.

Males are slightly smaller than females, but the surest way to tell sexes apart is by the fact that only males call and can inflate their yellow vocal sacs. Adults tend to live only for one year, but some have lived as many as three years.

Their tadpoles (the life stage between the egg and the adult) are grey or brown. Their body is round with a clear tail.

Keith Williams

Common Raven

Common Raven (15 seconds) Common Raven (Youth) Common Raven Common Raven (30 seconds)

Keith Williams

Common Raven

Common Raven (15 seconds) Common Raven (Youth) Common Raven Common Raven (30 seconds)

|

| Common Raven showing its hackles and large beak |

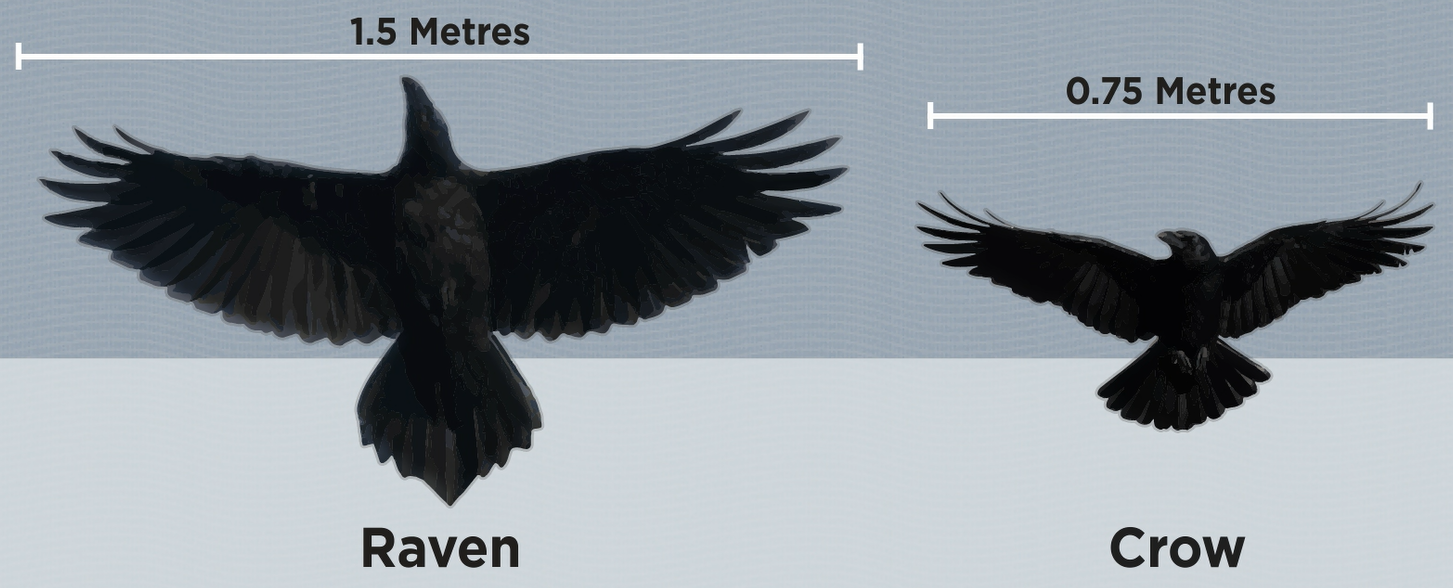

The Common Raven Corvus corax is one of the heaviest passerine birds and the largest of all the songbirds. It is easily recognizable because of its size (between 54 and 67 centimetres long, with a wingspan of 115 to 150 cm, and weighing between 0.69 and two kilograms) and its black plumage with purple or violet lustre. It has a ruff of feathers on the throat, which are called 'hackles', and a wide, robust bill. When in flight, it has a wedge-shaped tail, with longer feathers in the middle. While females may be a bit smaller, both sexes are very similar. The size of an adult raven may also vary according to its habitat, as subspecies from colder areas are often larger.

A raven may live up to 21 years in the wild, making it one of the species with the longest lifespan in all passerine birds.

|

| American Crow |

The Common Raven is often mistaken for an American Crow in southern Canada and the United States. Both birds are from the same genus (order of passerine birds, corvid family –like jays, magpies and nutcrackers, Corvus genus) and have a similar colouring. But the American Crow is smaller (with a wingspan of about 75 cm) and has a fan-shaped tail when in flight (with no longer feathers). It also has a narrower bill and lacks the raven’s hackles. Their cries are different: the raven produces a low croaking sound, while the crow has a higher pitched cawing cry. While adult ravens tend to live alone or in pairs, crows are more often observed in larger groups.

|

| Common Raven vs American Crow |

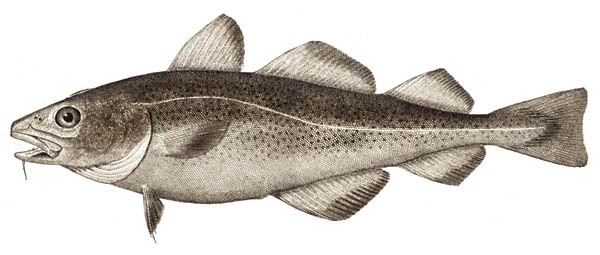

Atlantic Cod

Atlantic Cod (Youth) Atlantic Cod (15 seconds) Atlantic Cod (30 seconds) Atlantic Cod

Atlantic Cod

Atlantic Cod (Youth) Atlantic Cod (15 seconds) Atlantic Cod (30 seconds) Atlantic Cod

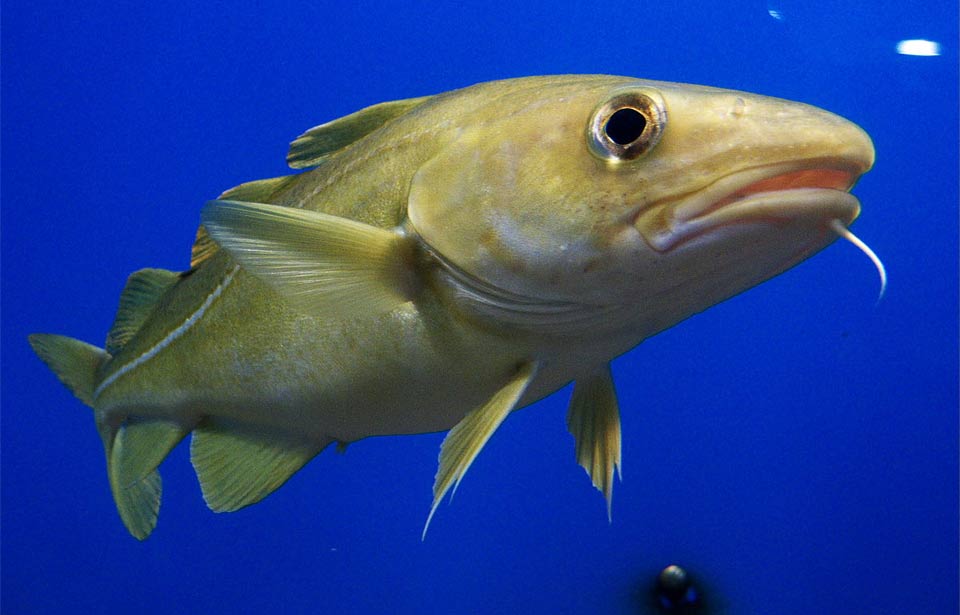

The Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) is a medium to large saltwater fish: generally averaging two to three kilograms in weight and about 65 to 100 centimetres in length, the largest cod on record weighed about 100 kg and was more than 180 cm long! Individuals living closer to shore tend to be smaller than their offshore relatives, but male and female cod are not different in size, wherever they live.

The Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) is a medium to large saltwater fish: generally averaging two to three kilograms in weight and about 65 to 100 centimetres in length, the largest cod on record weighed about 100 kg and was more than 180 cm long! Individuals living closer to shore tend to be smaller than their offshore relatives, but male and female cod are not different in size, wherever they live.

The Atlantic Cod shares some of its physical features with the two other species of its genus, or group of species, named Gadus. The Pacific Cod and Alaska Pollock also have three rounded dorsal fins and two anal fins. They also have small pelvic fins right under their gills, and barbels (or whiskers) on their chins. Both Pacific and Atlantic Cod have a white line on each side of their bodies from the gills to their tails, or pectoral fins. This line is actually a sensory organ that helps fish detect vibrations in the water.

The colour of an Atlantic Cod is often darker on its top than on its belly, which is silver, white or cream-coloured. Its exact colour varies between individuals and seems to depend on its habitat in order to camouflage, or blend in: when there’s lots of algae around, a cod can be reddish to greenish in colour, while a paler grey colour is more common closer to the sandy bottom of the ocean. In rocky areas, a cod may be a darker brown colour. Cod are often mottled, or have a lot of darker blotches or spots.

The Atlantic Cod may live as long as 25 years.

Moira Brown, New England Aquarium

North Atlantic Right Whale

North Atlantic Right Whale North Atlantic Right Whale (Youth) North Atlantic Right Whale (30 seconds) North Atlantic Right Whale (15 seconds)

Moira Brown, New England Aquarium

North Atlantic Right Whale

North Atlantic Right Whale North Atlantic Right Whale (Youth) North Atlantic Right Whale (30 seconds) North Atlantic Right Whale (15 seconds)

The North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalæna glacialis) is one of the rarest of the large whales. It can weigh up to 63,500 kilograms and measure up to 16 metres. That’s the length of a transport truck and twice the weight! Females tend to be a bit larger than males – measuring, on average, one metre longer. Considering its weight, it’s fairly short, giving it a stocky, rotund appearance. Its head makes up about a fourth of its body length, and its mouth is characterized by its arched, or highly curved, jaw. The Right Whale’s head is partially covered in what is called callosities (black or grey raised patches of roughened skin) on its upper and lower jaws, and around its eyes and blowhole. These callosities can appear white or cream as small cyamid crustaceans, called “whale lice”, attach themselves to them. Its skin is otherwise smooth and black, but some individuals have white patches on their bellies and chin. Under the whale’s skin, a blubber layer of sometimes more than 30 centimetres thick helps it to stay warm in the cold water and store energy. It has large, triangular flippers, or pectoral fins. Its tail, also called flukes or caudal fins, is broad (six m wide from tip to tip!), smooth and black. That’s almost the same size as the Blue Whale’s tail, even though Right Whales are just over half their size. Unlike most other large whales, it has no dorsal fin.

The North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalæna glacialis) is one of the rarest of the large whales. It can weigh up to 63,500 kilograms and measure up to 16 metres. That’s the length of a transport truck and twice the weight! Females tend to be a bit larger than males – measuring, on average, one metre longer. Considering its weight, it’s fairly short, giving it a stocky, rotund appearance. Its head makes up about a fourth of its body length, and its mouth is characterized by its arched, or highly curved, jaw. The Right Whale’s head is partially covered in what is called callosities (black or grey raised patches of roughened skin) on its upper and lower jaws, and around its eyes and blowhole. These callosities can appear white or cream as small cyamid crustaceans, called “whale lice”, attach themselves to them. Its skin is otherwise smooth and black, but some individuals have white patches on their bellies and chin. Under the whale’s skin, a blubber layer of sometimes more than 30 centimetres thick helps it to stay warm in the cold water and store energy. It has large, triangular flippers, or pectoral fins. Its tail, also called flukes or caudal fins, is broad (six m wide from tip to tip!), smooth and black. That’s almost the same size as the Blue Whale’s tail, even though Right Whales are just over half their size. Unlike most other large whales, it has no dorsal fin.

For a variety of reasons, including its rarity, scientists know very little about this rather large animal. For example, there is little data on the longevity of Right Whales, but photo identification on living whales and the analysis of ear bones and eyes on dead individuals can be used to estimate age. It is believed that they live at least 70 years, maybe even over 100 years, since closely related species can live as long.

Unique characteristics

The Right Whale has a bit of an unusual name. It is thought to have been named by whalers as the “right” whale to hunt due to its convenient tendencies to swim close to shore and float when dead. Its name in French is more straightforward; baleine noire, the black whale.

Parks Canada / Parcs Canada

American Eel

American Eel American Eel (30 seconds) American Eel (15 seconds) American Eel (Youth) Ocean Commotion (webisode)

Parks Canada / Parcs Canada

American Eel

American Eel American Eel (30 seconds) American Eel (15 seconds) American Eel (Youth) Ocean Commotion (webisode)

The American Eel (Anguilla rostrata) is a fascinating migratory fish with a very complex life cycle. Like salmon, it lives both in freshwater and saltwater. But its life-cycle is exactly the reverse of salmon’s: the eel is a catadromous species. It is born in saltwater and migrating to freshwater to grow and mature before returning to saltwater to spawn and die. The American Eel can live as long as 50 years.

It is a long, slender fish that can grow longer than one metre in length and 7.5 kilograms in weight. Males tend to be smaller than females, reaching a size of about 0.4 m. With its small pectoral fins right behind its gills, absence of pelvic fins, long dorsal and ventral fins and the thin coat of mucus on its tiny scales, the adult eel slightly resembles a slimy snake but are in fact true fish. Adult eels vary in coloration, from olive green and brown to greenish-yellow, with a light gray or white belly. Females are lighter in colour than males. Large females turn dark grey or silver when they mature.

It is known by a variety of names in Canada, including: the Atlantic Eel, the Common Eel, the Silver Eel, the Yellow Eel, the Bronze Eel and Easgann in Irish Gaelic. In Indigenous languages, like Mi’kmaq, it is known as k’at or g’at, the Algonquins call it pimzi or pimizì, in Ojibwe bimizi, in Cree Kinebikoinkosew and the Seneca call it goda:noh.

The American Eel is the only representative of its genus (or group of related species) in North America, but it does have a close relative which shares the same spawning area: the European Eel. Both have similar lifecycles but different distributions in freshwater systems except in Iceland, where both (and hybrids of both species) can be found.

Thinkstock

North American Lobster

North American Lobster North American Lobster (30-seconds) North American Lobster (youth) North American Lobster (15-seconds)

Thinkstock

North American Lobster

North American Lobster North American Lobster (30-seconds) North American Lobster (youth) North American Lobster (15-seconds)

The American Lobster (Homarus americanus) is a marine invertebrate which inhabits our Atlantic coastal waters. As an invertebrate, it lacks bones, but it does have an external shell, or exoskeleton, making it an arthropod like spiders and insects. Its body is divided in two parts: the cephalothorax (its head and body) and its abdomen, or tail. On its head, the lobster has eyes that are very sensitive to movement and light, which help it to spot predators and prey, but are unable to see colours and clear images. It also has three pairs of antennae, a large one and two smaller ones, which are its main sensory organs and act a bit like our nose and fingers. These antennae are able to smell the water to locate prey and touch elements in the lobster’s environment so it can find its way. The lobster’s mouth is located just below its eyes. Around its mouth are small appendages called maxillipeds and mandibles which help direct food to the mouth and chew. Food is then brought to the first of the lobster’s two stomachs, which is just inside its mouth! The lobster’s respiratory system is made of gills, like fish, which are situated on each side of its cephalothorax.

The lobster’s legs are also found on the cephalothorax. Lobsters have ten legs, making them decapod (ten-legged) crustaceans, a group to which shrimp and crabs also belong (other arthropods have a different number of legs, like spiders, which have eight, and insects, which have six). Four pairs of these legs are used mainly to walk and are called pereiopods. The remaining pair, at the front of the cephalothorax, are called chelipeds and each of those limbs ends with a claw. These claws help the lobster defend itself, but also capture and consume its prey. Each claw serves a different purpose: the bigger, blunter one is used for crushing, and the smaller one with sharper edges, for cutting. The claw used for crushing can be on the lobster’s right or left side, making it “right-handed” or “left-handed”. When a lobster’s limb, claw or antennae becomes damaged or lost, it is regrown when the lobster moults, a process called autotomy or regeneration. Hairs on the lobster’s legs and claws also act as sensory organs and are able to smell.

North American Lobster Missing A Claw

J.J. Cadiz

Barn Swallow

Barn Swallow (60 seconds) Barn Swallow (30 seconds)

J.J. Cadiz

Barn Swallow

Barn Swallow (60 seconds) Barn Swallow (30 seconds)

The Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica) is a medium-sized songbird, about the size of a sparrow. It measures between 15 and 18 centimeters (cm) in length and 29 to 32 cm in wingspan, and weighs between 15 and 20 grams (g). But while it is average-sized, it’s far from average-looking! Its back and tail plumage is a distinctive steely, iridescent blue, with light brown or rust belly and a chestnut-coloured throat and forehead. Their long forked tail and pointed wings also make them easily recognizable. It’s these wings, tail and streamlined bodies that make their fast, acrobatic flight possible. Both sexes may look similar, but females are typically not as brightly coloured and have shorter tails than males. When perched, this swallow looks almost conical because of its flat, short head, very short neck and its long body.

Although the average lifespan of a Barn Swallow is about four years, a North American individual older than eight years and a European individual older than 16 years have been observed.

Sights and sounds:

Like all swallows, the Barn Swallow is diurnal –it is active during the day, from dusk to dawn. It is an agile flyer that creates very acrobatic patterns in flight. It can fly from very close to the ground or water to more than 30 m heights. The species may be the fastest swallow, as it’s been recorded at speeds close to 75 kilometers per hour (km/h). When not in flight, the Barn Swallow can be observed perched on fences, wires, TV antennas or dead branches.

Both male and female Barn Swallows sing both individually and in groups in a wide variety of twitters, warbles, whirrs and chirps. They give a loud call when threatened, to which other swallows will react, leaving their nests to defend the area.

Thinkstock

Freshwater Turtles

Freshwater Turtles (30 seconds) Freshwater Turtles

Thinkstock

Freshwater Turtles

Freshwater Turtles (30 seconds) Freshwater Turtles

Stinkpot

Freshwater turtles are reptiles, like snakes, crocodilians and lizards. Like other reptiles, they are ectothermic, or “cold-blooded”, meaning that their internal temperature matches that of their surroundings. They also have a scaly skin, enabling them, as opposed to most amphibians, to live outside of water. Also like many reptile species, turtles lay eggs (they are oviparous). But what makes them different to other reptiles is that turtles have a shell. This shell, composed of a carapace in the back and a plastron on the belly, is made of bony plates. These bones are covered by horny scutes made of keratin (like human fingernails) or leathery skin, depending on the species. All Canadian freshwater turtles can retreat in their shells and hide their entire body except the Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina). This shell is considered perhaps the most efficient form of armour in the animal kingdom, as adult turtles are very likely to survive from one year to the next. Indeed, turtles have an impressively long life for such small animals. For example, the Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingi) can live for more than 70 years! Most other species can live for more than 20 years.

There are about 320 species of turtles throughout the world, inhabiting a great variety of terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems on every continent except Antarctica and its waters. In Canada, eight native species of freshwater turtles (and four species of marine turtles) can be observed. Another species, the Pacific Pond Turtle (Clemmys marmorata), is now Extirpated, having disappeared from its Canadian range. Also, the Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) has either such a small population that it is nearly Extirpated, or the few individuals found in Canada are actually pets released in the wild. More research is needed to know if these turtles are still native individuals. Finally, the Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), has been introduced to Canada as released pets and, thus, is not a native species.

Thinkstock

Little Brown Bat

Little Brown Bat (30 seconds) Little Brown Bat (60 seconds)

Thinkstock

Little Brown Bat

Little Brown Bat (30 seconds) Little Brown Bat (60 seconds)

Little Brown Bat

The Little Brown Bat, or Little Brown Myotis (Myotis lucifugus) weighs between 7 and 9 g, and has a wingspan of between 25 and 27 cm. Females tend to be slightly larger than males but are otherwise identical. As its name implies, it is pale tan to reddish or dark brown with a slightly paler belly, and ears and wings that are dark brown to black.

Contrary to popular belief, Little Brown Bats, like all other bats, are not blind. Still, since they are nocturnal and must navigate in the darkness, they are one of the few terrestrial mammals that use echolocation to gather information on their surroundings and where prey are situated. The echolocation calls they make, similar to clicking noises, bounce off objects and this echo is processed by the bat to get the information they need. These noises are at a very high frequency, and so cannot be heard by humans.

Glenn Williams

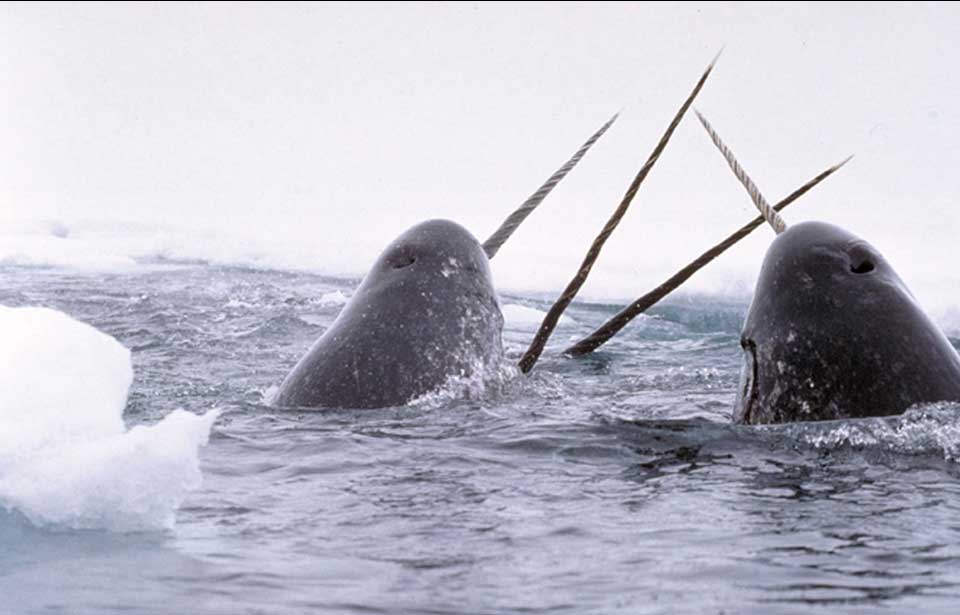

Narwhal

Narwhal (30 seconds) Narwhal (60 seconds)

Glenn Williams

Narwhal

Narwhal (30 seconds) Narwhal (60 seconds)

Narwhals (Monodon monoceros) are considered medium-sized odontocetes, or toothed whales (the largest being the sperm whale, and the smallest, the harbour porpoise), being of a similar size to the beluga, its close relative. Males can grow up to 6.2 m -the average size being 4.7 m- and weigh about 1,600 kg. Females tend to be smaller, with an average size of 4 m and a maximum size of 5.1 m and weigh around 900 kg. A newborn calf is about 1.6 m long and weighs about 80 kilograms. The narwhal has a deep layer of fat, or blubber, about 10 cm thick, which forms about one-third of the animal’s weight and acts as insulation in the cold Arctic waters.

Like belugas, they have a small head, a stocky body and short, round flippers. Narwhals lack a dorsal fin on their backs, but they do have a dorsal ridge about 5 cm high that covers about half their backs. This ridge can be used by researchers to differentiate one narwhal from another. It is thought that the absence of dorsal fin actually helps the narwhal navigate among sea ice. Unlike other cetaceans –the order which comprises all whales–, narwhals have convex tail flukes, or tail fins.

These whales have a mottled black and white, grey or brownish back, but the rest of the body (mainly its underside) is white. Newborn narwhal calves are pale grey to light brownish, developing the adult darker colouring at about 4 years old. As they grow older, they will progressively become paler again. The narwhal’s colouring gives researchers an idea about how old an individual is. Some may live up to 100 years, but most probably live to be 60 years of age.

The narwhal’s most striking feature is undoubtedly its tusk. This long, spiral upper incisor tooth (one of the two teeth narwhals have) grows out from the animal’s upper jaw, and can measure up to 3 m and weigh up to 10 kg. Although the second, smaller incisor tooth often remains embedded in the skull, it rarely but on occasion develops into a second tusk. Tusks typically grow only on males, but a few females have also been observed with short tusks. The function of the tusk remains a mystery, but several hypotheses have been proposed. Many experts believe that it is a secondary sexual character, similar to deer antlers. Thus, the length of the tusk may indicate social rank through dominance hierarchies and assist in competition for access to females. Indeed, there are indications that the tusks are used by male narwhals for fighting each other or perhaps other species, like the beluga or killer whale. A high quantity of tubules and nerve endings in the pulp –the soft tissue inside teeth – of the tusk have at least one scientist thinking that it could be a highly sensitive sensory organ, able to detect subtle changes in temperature, salinity or pressure. Narwhals have not been observed using their tusk to break sea ice, despite popular belief. Narwhals do occasionally break the tip of their tusk though which can never be repaired. This is more often seen in old animals and gives more evidence that the tusk might be used for sexual competition. The tusk grows all throughout a male’s lifespan but slows down with age.

Laurenz Baars

Downy Woodpecker

Laurenz Baars

Downy Woodpecker

Of the 198 species of woodpeckers worldwide, 13 are found in Canada. The smallest and perhaps most familiar species in Canada is the Downy Woodpecker Picoides pubescens. It is also the most common woodpecker in eastern North America.

This woodpecker is black and white with a broad white stripe down the back from the shoulders to the rump. Its wings are checkered in a black and white pattern that shows through on the wings’ undersides, and the breast and flanks are white. The crown of the head is black; the cheeks and neck are adorned with black and white lines. Male and female Downy Woodpeckers are about the same size, weighing from 21 to 28 g. The male has a small scarlet patch, like a red pompom, at the back of the crown.

The Downy Woodpecker looks much like the larger Hairy Woodpecker Picoides villosus, but there are some differences between them. The Downy’s outer tail feathers are barred with black, unlike the Hairy Woodpecker’s, which are all white. The Downy is about 6 cm smaller than the Hairy, measuring only 15 to 18 cm from the tip of its bill to the tip of its tail. And the Downy’s bill is shorter than its head, whereas the Hairy’s bill is as long as or longer than its head length. The Downy’s name refers to the soft white feathers of the white strip on the lower back, which differ from the more hairlike feathers on the Hairy Woodpecker.

Woodpeckers are a family of birds sharing several characteristics that separate them from other avian families. Most of the special features of their anatomy are associated with the ability to dig holes in wood. The straight, chisel-shaped bill is formed of strong bone overlaid with a hard covering and is quite broad at the nostrils in order to spread the force of pecking. A covering of feathers over the nostrils keeps out pieces of wood and wood powder. The pelvic bones are wide, allowing for attachment of muscles strong enough to move and hold the tail, which is important for climbing.

Another special anatomical trait of woodpeckers is the long, barbed tongue that searches crevices and cracks for food. The salivary glands produce a sticky, glue-like substance that coats the tongue and, along with the barbs, makes the tongue an efficient device for capturing insects.

Signs and sounds

As early as February or March a Downy Woodpecker pair indicate that they are occupying their nesting site by flying around it and by drumming short, fast tattoos with their bills on dry twigs or other resonant objects scattered about the territory. The drumming serves as a means of communication between the members of the pair as well. Downys also have a variety of calls. They utter a tick, tchick, tcherrick, and both the male and the female add a sharp whinnying call during the nesting season.

Hatchlings give a low, rhythmic pip note, which seems to indicate contentment. When a parent enters the nest cavity, the nestlings utter a rasping begging call, which becomes stronger and longer as the chicks mature.

John Williams

Redhead

John Williams

Redhead

The Redhead Aythya americana is a well-known and widely distributed North American diving duck. The adult male is a large, grey-backed, white-breasted duck with a reddish-chestnut head and black neck and chest. It resembles the larger male Canvasback. At close range, the head appears puffy, with an abrupt forehead and a short, broad bill, while the Canvasback’s bill is longer and slopes down from the forehead. The adult female is a large, brown-backed, white-breasted duck with a brown head, whitish chin, abrupt forehead, short, broad bill, and pearl-grey wing patches. Female Redheads, although larger, may be confused with female Ring-necked Ducks and scaups.

In autumn young Redheads resemble adult females, although their breast plumage is dull grey-brown, rather than white. During November and December, the young begin to develop the adult plumage, which has almost completely grown in by February.

The genus Aythya, to which the Redhead belongs, includes 12 species, all of which are well adapted to diving. The body is rounded and thick with large feet, legs set back on the body, and a broad bill. Body shapes vary from the big, long-necked, long-billed Canvasback to the short-billed scaup. The genus is represented in North America by the Canvasback, Redhead, Greater Scaup, Lesser Scaup, and Ring-necked Duck.

Bill Maynard

Trumpeter Swan

Trumpeter Swan Wetlands (30 seconds) Wetlands (60 seconds)

Bill Maynard

Trumpeter Swan

Trumpeter Swan Wetlands (30 seconds) Wetlands (60 seconds)

Adult Trumpeter Swans Cygnus buccinator are large birds with white feathers and black legs and feet. The feathers of the head and the upper part of the neck often become stained orange as a result of feeding in areas rich in iron salts. The lack of colour anywhere on the swans’ bodies distinguishes them from other white species of waterfowl, such as snow geese, which have black wing tips.

Adult Trumpeter Swans Cygnus buccinator are large birds with white feathers and black legs and feet. The feathers of the head and the upper part of the neck often become stained orange as a result of feeding in areas rich in iron salts. The lack of colour anywhere on the swans’ bodies distinguishes them from other white species of waterfowl, such as snow geese, which have black wing tips.

The male swan, or cob, weighs an average of 12 kg. The female, or pen, is slightly smaller, averaging 10 kg. Wings may span 3 m. Young of the year, or cygnets, can be distinguished from adults by their grey plumage, their yellowish legs and feet, and until their second summer of life, their smaller size.

The shape and colour of the bill help in identifying the Trumpeter and Tundra swans in the field. Trumpeters have all black bills; Tundra Swans, formerly called Whistling Swans, have more sloping bills, usually with a small yellow patch in front of the eye. If this patch is missing, it is quite difficult to distinguish between the two birds unless the voice is heard. At close range, an observer should look for a salmon-red line on the lower bill.

A third type of swan, the Eurasian Mute Swan, is often seen in Canadian parks and zoos. The Mute is all white with a black knob on a reddish-orange and black bill. The Trumpeter Swan is the largest of the three species.

Signs and sounds

Although very similar in appearance, the Trumpeter Swan and the Tundra Swan have quite different voices. The Trumpeter Swan has a deep, resonant, brassy, trumpet-like voice; the voice of the Tundra Swan is softer and more melodious.