Description

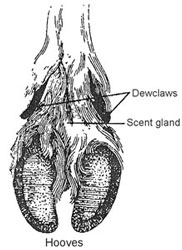

Figure 1: Base of caribou foot

The caribou Rangifer tarandus is a medium-sized member of the deer family, Cervidae, which includes four other species of deer native to Canada: moose, elk, white-tailed deer, and mule deer. All are ungulates, or cloven-hoofed cud-chewing animals. However, only in caribou do both males and females carry antlers. Caribou are similar to and belong to the same species as the wild and domesticated reindeer of Eurasia.

The caribou is well adapted to its environment. Its short, stocky body conserves heat, its long legs help it move through snow, and its long dense winter coat provides effective insulation, even during periods of low temperature and high wind. The muzzle and tail are short and well haired.

Large, concave hooves splay widely to support the animal in snow or muskeg, and function as efficient scoops when the caribou paws through snow to uncover lichens and other food plants. In fact, the name “caribou” may be linked to this ability—it may be a corruption of the Mi’kmaq name for the animal, “xalibu,” which means “the one who paws.” The sharp edges give firm footing on ice or smooth rock. Caribou are excellent swimmers and their hooves function well as paddles. In winter, the hooves grow to a remarkable length, giving the animal firm footing on crusty snow. In summer, the hooves are worn away by travel over hard ground and rocks. The dewclaws, or small toes, are large, widely spaced, and set back on the foot, greatly increasing the weight-bearing area. Scent glands located at the base of the ankles are used when the caribou is in danger: the animal rears up on its hind legs and deposits a scent that alerts other caribou to the menace. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 2: Caribou antlers

In the autumn, the caribou male, or bull, is an imposing animal. It has a rich brown or grey and white coat, a fringe of white hair flowing from throat to chest, and a great rack of amber-coloured antlers. Antler growth starts each year in the spring and is typically complete by late August. Adult bulls generally shed their antlers in November or December, after they have mated. Adult females, or cows, and young animals carry their antlers much longer, often through the winter. The growing antlers have a fuzzy covering, called velvet, which contains blood vessels carrying nutrients for growth. (See Figure 2.)

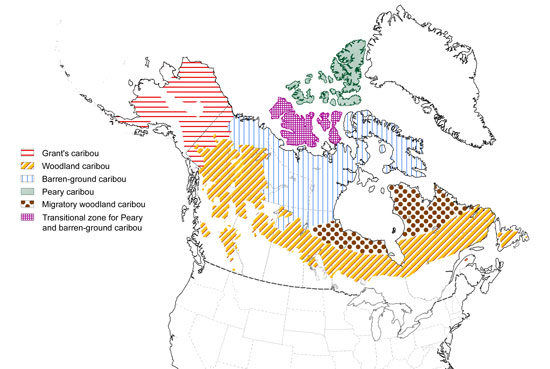

Four subspecies of caribou occur in Canada: woodland (Rangifer tarandus caribou), Peary (Rangifer tarandus pearyi), barren-ground west of the Mackenzie River (Rangifer tarandus granti), also known as Grant’s caribou, and barren-ground east of the Mackenzie River (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus). A fifth subspecies, Dawson’s or the Queen Charlotte Islands population of woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus dawsoni), died out in the 1930s and was declared extinct in 1984.

Signs and sounds

Caribou are usually quiet, but they may give a loud snort. Herds of snorting caribou may sound like pigs. Especially vocal are the bands of cows and new-born calves, constantly communicating with each other.

Habitat and Habits

There are more than 2.4 million caribou in Canada. Some dwell in forests, some in mountains, some migrate each year between the sparse forests and tundra of the far north, and others remain on the tundra all year.

Peary caribou

Photo: B.T. Aniskowicz-Fowler

Barren-ground caribou

Photo: Canadian Wildlife Service

The woodland caribou is the largest and darkest of the caribou subspecies. It is found throughout much of the boreal, or northern, forests from British Columbia and the Yukon Territory to Newfoundland and Labrador. In mountainous areas of western Canada, woodland caribou make seasonal movements from winter range on forested mountainsides to summer range on high, alpine tundra. Farther east, in the more level areas of boreal forest, many woodland caribou occupy mature forest and open bogs and fens, or low-lying wet areas. Some may move only a few kilometres seasonally, while others may wander extensively. A few herds differ from this pattern, making long seasonal movements between forested and tundra habitats. The Leaf River and George River herds in Quebec and Labrador are the largest of these herds. They are also among the biggest caribou herds in North America, at about 600 000 and 400 000 individuals respectively.

Peary caribou are small, light-coloured caribou found only in the islands of the Canadian arctic archipelago, where they number about 10 000. Peary caribou do not normally have significant migrations, although many move among islands, especially if hard icing conditions force them from their normal ranges.

About half of all caribou in Canada are barren-ground caribou. They are somewhat smaller and lighter coloured than woodland caribou. They spend much or all of the year on the tundra from Alaska to Baffin Island. Most, or about 1.2 million, of the barren-ground caribou in Canada live in eight large migratory herds, which migrate seasonally from the tundra to the taiga, sparsely treed coniferous forests south of the tundra. In order, from Alaska to Hudson Bay, these are the Porcupine herd, Cape Bathurst herd, Bluenose West herd, Bluenose East herd, Bathurst herd, Ahiak herd, Beverly herd, and Qamanirjuaq herd. About 120 000 other barren-ground caribou live in smaller herds that spend the entire year on the tundra. Half of these are confined to Baffin Island.

Range

Distribution of caribou

In Canada, caribou are found from the United States–Canada boundary to northern Ellesmere Island, more than 4 000 km north, and from British Columbia and the Yukon Territory in the west to the island of Newfoundland in the east. The southern limit of caribou distribution has receded northward since European settlement and this recession continues today.

Feeding

Ground and tree lichens are the primary winter food of caribou, providing a highly digestible and energy-rich food source. The ability of caribou to use lichens as a primary winter food distinguishes them from all other large mammals and has enabled them to survive on harsh northern rangeland. Caribou use their excellent sense of smell to locate lichens under the snow, and they dig the lichens out with their wide hooves. In southern coniferous forests they are also able to forage on tree lichens.

Although lichens are a good source of energy, they are not a good source of protein (nitrogen). As soon as spring snow melts, caribou are eager to switch to fresh green vegetation, which is rich in nitrogen. Cows that have just given birth are especially in need of protein to replenish their protein reserves and produce high quality milk for their calves. At this time of year caribou focus on sedges and newly unfurling leaves of willow and other shrubs. Flowers, plentiful on the tundra, also attract a lot of attention. As summer progresses and the quality of the green vegetation declines, caribou once again turn to lichens, to fatten themselves up for the breeding season. Although not always available, mushrooms are highly sought after in August and September. Mushrooms provide a rich nitrogen source late in the summer.

Breeding

Although all caribou move about for different functions over the course of a year, barren-ground caribou make the most dramatic treks. They are the most efficient walkers of all ungulates in North America, and they are good navigators, unerringly walking hundreds of kilometres from the taiga to their relatively small calving areas on the tundra in spring. They tend to follow frozen lakes and rivers, open snow-free uplands, and eskers, or long narrow hills of soil and rock dumped by glaciers. Caribou are able to keep a steady direction across frozen lakes so large that the opposite shore cannot be seen.

Pregnant barren-ground caribou cows lead the spring migration, followed by juveniles, bulls, and non-pregnant cows, which tend to lag farther and farther behind. Barren-ground caribou cows head toward traditional calving grounds, where they gather to calve year after year, even from different wintering areas.

In contrast, to avoid predation smaller woodland herds generally calve in isolation either in rugged terrain or on islands in small lakes.

Caribou cows are usually at least three years old before they can bear young, though 10 to 25 percent of two-year-old cows can also give birth. Cows produce one calf a year, and about 90 percent of adult cows give birth annually. Most of the calves are born during a 10-day period in May or early June. Calving time tends to be later the further east in North America the caribou are found.

The calves are well developed at birth and are able to travel within a few hours. They start to graze during their first weeks, but until they are about three weeks old, they can digest only milk. The cows and calves soon move to areas where fresh-growing feed is becoming abundant.

During summer barren-ground caribou are often harassed by hordes of mosquitoes, warble flies, caribou nostril flies and, in some areas, black flies. Sometimes the agitated animals will run for many kilometres, stopping to rest only when exhausted or when high winds temporarily disperse the insects. Running from insects places great energy demands on the caribou and may slow their rate of growth by temporarily reducing their search for food. In large herds, another strategy to reduce harassment of individual animals is to form large gatherings of caribou. These tight groups can number in the tens of thousands.

By late September the herds, fat and in good condition, arrive in pre-rutting (pre-mating) areas. The rut occurs from mid-September to early November depending on the region. Bulls spar a great deal and sometimes fight for possession of cows. Normally, during the rut, cows will wean their calves, encouraging them to eat food other than their mothers’ milk. If the calf is too small, the cow will continue to supply milk into the winter, but this reduces her chances of getting pregnant that autumn.

In the deer family, antler size means dominance. By late winter when conditions are most severe, pregnant females are the dominant members of the herd, because they are the only ones to have retained their antlers. The large bulls lose their antlers after the autumn mating season, and the non-breeders lose theirs soon after that. The females’ dominance allows them to defend their feeding craters from larger caribou and even displace larger caribou from favoured sites. This is important when conditions are harsh, as the pregnant cows need energy to develop the fetus. Most pregnant females will keep their antlers until after they give birth in June.

Conservation

Population status

Despite the large number of caribou in Canada, some subspecies or populations have been determined to be at risk by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC).

Dawson’s or the Queen Charlotte Islands population of woodland caribou, found only on Graham Island, British Columbia, has been designated extinct. Little is known of this greyish-coloured subspecies or of the causes of its extinction, but while deterioration of habitat due to climate change may have been a factor, a more important cause was likely overhunting.

Woodland caribou became extirpated from (no longer exist in) Prince Edward Island before 1873 and from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia by the 1920s. Today only a small, relic herd on the Gaspé Peninsula remains of the maritime woodland caribou population south and east of the St. Lawrence River. This Atlantic-Gaspésie population has been assessed as endangered by COSEWIC and is listed under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). A species is considered endangered when it is facing imminent disappearance from Canada or extinction.

The widespread Boreal population of woodland caribou, which occurs in the Northwest Territories, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador, has been assessed as threatened by COSEWIC and is listed under SARA. The Southern Mountain population of woodland caribou, which occurs in British Columbia and Alberta, has also been assessed and listed as threatened. A threatened species is one that is likely to become endangered if nothing is done to reverse the factors limiting its survival in Canada.

COSEWIC has assessed the Northern Mountain population of woodland caribou, which occurs in the Yukon Territory, the Northwest Territories, and British Columbia, as being of special concern. It is also listed under SARA. A species of special concern is one that may become threatened or endangered because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

The Peary caribou has been assessed as endangered by COSEWIC. Consultations are underway to determine if Peary caribou should be listed under SARA. Numbers have declined by about 72 percent in the last 60 years, mostly because of severe icing episodes due to changing weather conditions, where ice has covered vegetation and led to caribou starvation.

One population of barren-ground caribou, the Dolphin and Union population in Nunavut, has also been assessed as a species of special concern by COSEWIC, and consultations are taking place to determine whether it should be listed under SARA. These caribou migrate between the mainland and Victoria Island; climate change and increased shipping may make this ice crossing more dangerous.

Recovery measures

There are national recovery teams, draft recovery plans, and coordinated recovery actions underway for the Peary caribou and the four populations of woodland caribou that are at risk: Atlantic-Gaspésie, Boreal, Southern Mountain, and Northern Mountain. Since the range of the Boreal population is so extensive, there are also regional recovery teams in place in each of the eight provinces and territories that have responsibility for “boreal caribou.”

Caribou are susceptible to and recover slowly from population declines because of their low rate of reproduction. The main factors leading to caribou declines are habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation, as well as predation. Loss of caribou habitat, which is permanent, occurs when forest is cleared for agriculture, for example. Habitat degradation means a reduction in the amount or quality of caribou habitat, as happens following such events as wildfires or timber harvesting, or through human disturbance. Habitat fragmentation is the breaking up of habitat areas by roads, timber harvest cut-blocks, pipelines, oil and gas well sites, geophysical exploration lines, and other developments.

Caribou in the boreal forest require large tracts of relatively undisturbed, older forest habitat in order to spread out so they are harder for predators and hunters to find, and to avoid the linear corridors that predators and hunters use to gain easier access to their prey. Older forests tend to be richer than younger forests in the lichens caribou depend on. They are also less favoured by moose and deer, which as prey species of the wolf, attract this primary predator of caribou.

A wolf eats a variety of prey but requires food equivalent to 11 to 14 caribou a year. Some wolf packs will follow migrating herds of caribou from summer to winter range and back. Other predators of caribou include grizzly and black bears, cougars, wolverines, lynx, coyotes, and golden eagles.

Partly as a result of habitat changes caused by humans, white-tailed deer have expanded into caribou areas from Manitoba to Quebec, transmitting meningeal brain worm, which is fatal to caribou, although it does not harm the deer. Insects such as warble flies, mosquitoes, and black flies also transmit disease to caribou, and internal parasites affect their health and condition.

Recently there has also been a lot of concern about the potential impact of climate change on caribou, especially in the north. Deeper snow, faster spring melt, warmer summers, freezing rain, and the high annual variability of all these factors will have an impact on the ability of the species to thrive in its environment.

Cultural and economic importance of caribou

Humans have a long association with caribou. Archaeological work in the Yukon Territory suggests humans have been hunting caribou for more than 13 000 years. Many Aboriginal peoples and Inuit based their culture on the caribou, and could not have survived in the north without them. Some tribes were nomadic, following the herds year-round; others lived on caribou for part of the year. Caribou provided food, clothing, and shelter: bones were made into needles and utensils, antlers into tools, and the sinew into thread; the fat provided fuel and light; the skin was made into light, warm clothing and tent material; and the flesh fed people and dogs. Wisely used, caribou will continue to be an important social and economic resource in the North.

Wildlife tourism is important in many parts of Canada occupied by caribou. Recreational hunting of forest-dwelling woodland caribou is of economic importance in the Yukon Territory, northern British Columbia, and Newfoundland and Labrador. In the north, vast herds of migrating caribou present a wildlife spectacle unequalled on this continent and, as an attraction to naturalists, photographers, and licensed hunters, could contribute to a tourist industry.

Resources

Online resources

Recovery Strategy for the Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou), Boreal Population, in Canada

Parks Canada, Species at Risk, Woodland Caribou

Print resources

Bergerud, A. T. 1978. Caribou. In J. L. Schmidt and D. L. Gilbert, editors. Big game of North America: ecology and management. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Calef, G. 1981. Caribou and the barren-lands. Firefly Books Ltd., Toronto.

Kelsall, J. P. 1968. The migratory barren-ground caribou of Canada. Monograph No. 3. Canadian Wildlife Service, Ottawa.

Kofinas, G., and D. Russell. 2004. North America. In B. Ulvevadet and K. Klokov, editors. Family-based reindeer herding and hunting economies, and the status and management of wild reindeer/caribou populations. Arctic Council Report. University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway.

Miller, F. L. 1982. Caribou. In J A. Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, editors. Wild animals of North America: biology, management and economics. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Russell, D. E., and A. M. Martell. 1984. The winter ecology of caribou (Rangifer tarandus). In R. Olson, F. Geddes, and R. Hastings, editors. Northern Ecology and Resource Management. University of Alberta Press, Edmonton.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1985, 1993, 2005. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/24-2005E-HTML

ISBN 0-662-39659-6

Revision: F. L. Miller, 1992; M. Rothfels and D. Russell, 2005

Editing: Maureen Kavanagh, 2005

Photos: Shane P. Mahoney; B.T. Aniskowicz-Fowler; Canadian Wildlife Service

| This fact sheet has been produced with the generous support of |  |