Description

The North American bison, or buffalo, is the largest land animal in North America. A bull can stand 2 m high and weigh more than a tonne. Female bison are smaller than males.

The North American bison, or buffalo, is the largest land animal in North America. A bull can stand 2 m high and weigh more than a tonne. Female bison are smaller than males.

A bison has curved black horns on the sides of its head, a high hump at the shoulders, a short tail with a tassel, and dense shaggy dark brown and black hair around the head and neck. Another distinctive feature of the buffalo is its beard.

There are two living subspecies of wild bison in North America: the plains bison Bison bison bison and the wood bison Bison bison athabascae.

The drawings show some of the features that biologists look for if they wish to identify a bison by subspecies. In general, the plains bison is lighter in colour than the wood bison. The wood bison is taller, longer legged, and less stockily built than the plains bison, but it is heavier.

Signs and sounds

During the mating season, from July to mid-September, “bull roarings” are heard for kilometres, day and night, as bulls challenge each other in the rutting ritual of the mating season.

Habitat and Habits

Historically, bison were known to make movements of up to hundreds of kilometres to take advantage of the changing availability of food plants in different seasons. These movements were most pronounced on the Great Plains, where large herds moved long distances along traditional routes. Some of these routes are still visible from the air in the form of deep paths worn over the years in the prairie soil by millions of passing hooves. In contrast, the wood bison in the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary in the Northwest Territories make only local movements during the year, moving between open meadows and the surrounding forest, in patterns established through traditional use.

Most bison live in mixed herds of cows, calves, yearlings, subadults, and a few bulls. The other bulls form groups of their own.

The most dangerous season for wild bison is the spring, with the melting of lake and river ice. The buffalo habit of bunching tightly together, safe enough on hard winter ice, often proves fatal in spring conditions, and enormous numbers died when great herds were common. On one day in 1795, a fur trader counted 7 360 drowned individuals in a tributary of the Red River, west of Winnipeg. In recent decades large numbers have drowned in the Peace-Athabasca Delta region of Wood Buffalo National Park.

As summer approaches, buffalo shed their thick winter coats. It is two months before the new coat appears. During this interval, which is the peak of the fly season, the buffalo wallow in marshes or dust bowls to escape from flies.

Fall is the best season for the buffalo. The flies are gone and the animals fatten rapidly as they prepare for the long cold season ahead. Winter poses few problems for bison. Their winter coats, reinforced by a heavy mane over the vital organs, protect them from the cold, and they can find nourishing grasses and sedges by swinging their heads from side to side to push away the snow. The buffaloes’ instincts protect them in blizzards, as they move into the wind instead of drifting with it like domestic cattle (which are sometimes crushed against fences and killed).

Unique characteristics

In the days when they grazed on the grasslands in huge numbers, plains bison greatly influenced the ecology of their habitat. Their wallows became temporary ponds in spring and home to a variety of water-loving creatures, such as ducklings and frogs. Their grazing encouraged the growth of grasses that flourish when the vegetation is short. Their heavy grazing coupled with dung production may have been a major factor in building the deep, rich organic soils of the prairies.

Bison herds are alert and quick to detect changes in their environment. Bison have keen senses of smell and hearing; they can distinguish smells from 3 km away.

Range

The map shows the bison’s present, historic, and prehistoric distribution.

The map shows the bison’s present, historic, and prehistoric distribution.

Two hundred years ago, the plains bison was by far the more common of the two subspecies. It was the dominant grazing animal of the interior plains of the continent, and it often occurred in large herds. A smaller population occurred east of the Mississippi.

Today, there are comparatively few plains bison. A herd of about 600 is fenced in at Elk Island National Park, 64 km east of Edmonton. There are small numbers at Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan, Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba, and Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta. There are at least 25 herds of plains bison in national and state parks and wildlife refuges in the United States, numbering more than 10 000 animals. There are more than 140 000 in private collections and on a large number of commercial ranches in both Canada and the United States.

The wood bison has always lived to the north of its prairie cousin. In historic times its range was centred in northern Alberta and the adjacent parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and Saskatchewan. Herds made use of aspen parkland, the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains, the lowlands of the Peace and Slave rivers, and the coniferous forests and wetland meadows of the upper Mackenzie Valley. The wood bison was never as abundant as the plains bison, probably numbering no more than 170 000 at its peak.

In April 1994, there were approximately 3 000 wood bison in Canada, most in five “free-roaming” herds, the largest of which consists of more than 2 000 animals in the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary near Fort Providence, Northwest Territories. The source herd of 350 animals for the recovery program is at Elk Island National Park. The total population is small enough that the wood bison is considered threatened by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC).

The other large free-roaming herd of bison is in Wood Buffalo National Park, on the Northwest Territories–Alberta border, where there are about 2 000 animals, descendants of mixed plains and wood bison stock.

Feeding

The grazing habits of bison are similar to those of domestic cattle. Bison eat grasses, sedges, and other ground-growing plants. In the days of free-roaming herds, the plains bison fed on a variety of native grasses, which had great nutritional value. In northern areas, the wood bison fed on a wide variety of grasses and wild forages, but mainly on meadow sedge, an abundant lowland forage, or food suitable for livestock. In winter, they would also eat the tender twigs of scrubland bushes.

Breeding

During the mating season, from July to mid-September, the herds move restlessly as bulls challenge each other in the rutting ritual of the mating season.

Most calves are born in May and June, one to each adult female every one or two years. The newborns are tawny yellow with only a faint suggestion of the shoulder hump. Both parents care for their calf to a certain extent, but in the face of danger the calf may be abandoned. The calves, however, rapidly gain in strength and agility, and by autumn they are able to keep up with the herd.

Buffalo take about eight years to mature and can live for up to 20 years in the wild. A few have survived past 30 years in captivity.

Conservation

|

|

Photo: iStockphoto.com/Rob Freeman

|

Two hundred years ago, anywhere from 30 to 70 million bison roamed free in North America. The aboriginal people who lived on the Great Plains relied on these wild mammals for food, clothing, and shelter.

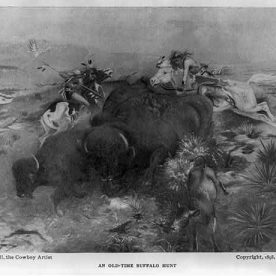

When buffalo were still plentiful, the Plains Indians ate buffalo meat and made their clothing and their tepees from buffalo hides. The native hunters took advantage of the bisons’ stampeding behaviour. They drove them over cliffs and into canyons. They often killed 50 or 60 at a time, for it was practically impossible to cut out the needed few from the tightly massed herd. Nevertheless, buffalo remained abundant.

The arrival of European settlers destroyed this way of life. During the late 1800s, commercial hide hunters, settlers, and thrill seekers shot millions of bison. In those days of unlimited hunting, bison herds were seen to smother in snow in their efforts to escape from humans. Panic-stricken by their enemies, the herds would also stampede over steep banks or into swamps.

The destruction of the vast free-ranging bison herds on the prairies brought the species to the verge of extinction[Hyperlink to the glossary.]and with it the collapse of the civilization of the Plains Indians. In so doing, it cleared the way for prairie agriculture.

Since about 1900, the population of bison in North America has increased, but not to anything near its original numbers. Two measures in particular have helped the plains bison recover to a certain extent: legal protection from hunting and ranchers’ raising of bison as livestock.

Strictly regulated hunting is a useful management tool. Recreational hunting of wild bison bulls is allowed in the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary, and long-time territorial residents can obtain a licence to hunt bison anywhere in the Northwest Territories except in Wood Buffalo National Park.

Because domesticated bison coexist more easily than wild ones with modern prairie life, many bison on the prairies exist on ranches, as livestock. Farmers appreciate the fact that bison are better adapted to prairie droughts and harsh winters than European cattle. Some farmers may also recognize that, because plains bison evolved as part of prairie grassland ecosystems, domesticated bison are potentially more compatible than beef cattle with the region’s other native animals and plants. Whether efforts to halt the decline of biodiversity and restore functioning native mixed-grass ecosystems on the prairies will eventually lead to the restoration of herds of wild and semi-wild plains bison to more of their former ranges remains to be seen.

North American bison are still under threat from other sources. Grizzly bears, black bears, grey wolves, and cougars have been known to prey on bison. The grizzly bear was and would still be a deadly enemy, but neither it nor the formidable cougar are numerous in buffalo territory today. Wolves are a danger chiefly to the young, the sick, and the old, because a buffalo in its prime is usually a match for wolves.

Many bison in northern Canada range freely in protected areas. Unfortunately, the wild bison in and around Wood Buffalo National Park (an area that includes over 40 percent of the wood bison’s former range) are infected with bovine tuberculosis and brucellosis, making it impossible to re-establish healthy wood bison herds in this habitat.

Bovine tuberculosis and brucellosis are diseases that were brought to North America by European cattle and passed to their relatives, the bison. The first evidence of tuberculosis in plains bison in Canada was at the Buffalo Park near Wainwright, Alberta, in the 1920s. When that park became overcrowded, 6 673 plains bison were moved north to Wood Buffalo National Park between 1925 and 1928. These animals apparently carried both brucellosis and tuberculosis, which continue to affect the free-ranging herds of mixed wood and plains bison in and around Wood Buffalo National Park.

These herds, and the wood bison in the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary, have also experienced sporadic outbreaks of anthrax, a disease caused by a bacterium that can survive in the soil for decades. Animals that become infected usually die, but anthrax is not carried or harboured by the bison themselves, except during outbreaks of active infection.

When infected animals stray away from the vicinity of the park, these diseases can be transmitted to other disease-free wood bison and to cattle. Cattle ranchers, park officials, aboriginal people, environmental groups, and government agencies with responsibilities for wildlife are trying to work out how best to conserve wild bison and protect the livelihood of the ranchers.

Resources

Online resources

Plains Bison, Species at Risk Registry

Wood Bison, Species at Risk Registry

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada

Print resources

Banfield, A.W.F. 1974. The mammals of Canada. University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Burnett, J.A., C.T. Dauphiné, Jr., S.H. McCrindle, and T. Mosquin. 1989. Wood bison. In On the brink: Endangered species in Canada. Western Producer Prairie Books, Saskatoon.

Federal Environmental Assessment Review Office. 1990. Northern diseased bison. Report of the Environmental Assessment Panel, Ottawa.

Foster, J., D. Harrison, and I.S. MacLaren. 1992. Buffalo. The University of Alberta Press, Edmonton.

Nikiforuk, A. 1992. Wild about buffalo. Harrowsmith 17(4):46–53.

Roe, F.G. 1970. The North American buffalo. University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Sandoz, M. 1954. The buffalo hunters. Hastings House, New York.

Seton, E.T. 1929. Lives of game animals. Doubleday, New York.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 1974, 1980, 1994. All rights reserved.

Catalogue number CW69-4/45-1994E

ISBN 0-662-22629-1

Revision: J.A. Keith and H. Reynolds, 1994